A brief excerpt:

“Immanuel, my dearest friend,

I cannot tell you how many hours I debated sending this correspondence. I am fearful that it has been much too long since our parting. For decades I convinced myself that you had forsaken me. My self-decided isolation was my retribution for abandoning you after the war. In truth, I hope you believed me dead; that would be easier than facing the truth of my own cowardice. However, I am compelled to expose myself to you at last as the man who ran yet returns contrite. Thus, I have arrived at my current state: convinced that this will be sent in vain. I fear I have injured you deeply and that this letter will remain unanswered, if opened at all.“

…

“Marcus,

Though I fare better with work than words, I doubt even W.C. Bryant could rightly tell you of my joy upon receiving your letter or of my pain at its contents. Would that I could see you and offer some sort of commiseration worth more than this scrap of paper; still, I do hope that it suffices as you say.”

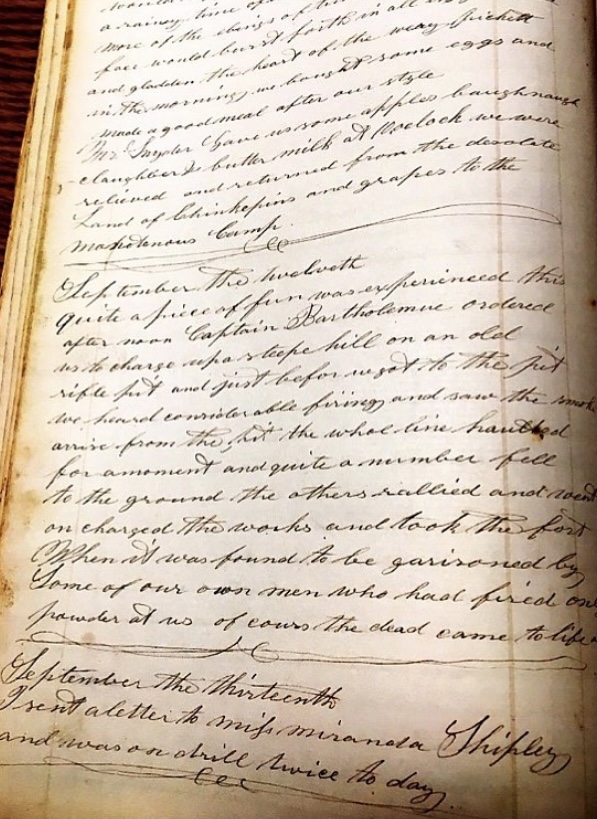

(Text is not representative of text on image. Image is a page from the journal of a Civil War soldier, courtesy of the Historical Society of Carroll County)

Hi everyone!

We’ll get back to the quotes in the intro, I promise! But first, while surveying people about what I should post about next, one of my friends asked if I could write something on how to form well-rounded characters. Honestly, I was a bit hesitant. One of my biggest fears as a writer is that my characters all come across as a bit one-note or that, even if they are “well-rounded” they’re all too similar to seem like unique people. However, I think the fact that I do worry about that so much has made me contemplate the nuances of character building enough to speak up on the matter.

Before diving in, I’m going to pull the typical-blog-thing and tell a brief story. When I started in the MFA program at Arcadia University the very first story I submitted was a historical fiction epistolary piece comprised of letters exchanged by two men of similar age and military background. The exchange quoted at the top of this blog is taken from that story.

I was absolutely terrified that people were going to say the voices of each letter sounded too similar to each other. When the time for critiques came, what people actually said was that they were impressed by how distinct each voice was.

To be frank, I was dumbfounded. Happy, but still shocked.

Looking back on it, however, I think that was my first realization of how I had taken extra steps to really make the characters into real individuals. Now, of course, all of this advice is just my own experience. Different people work in different ways and what works for me may not work for you. That being said, the biggest piece of advice I can give about forming well-rounded characters is this:

The author should always know more about their characters than the reader.

That’s pretty obvious advice, I know none of us want to bore our readers with all of the random character details floating around in our heads, but there are a few different ways of going about it and that is really what I’m here to get into.

One approach that I see a lot, in comic writing especially, is to fill out character sheets. These can contain prompts for anything and everything from “What is the character’s favorite color?” to “How do they act at a funeral?” (I just made those up but if you want an example of an in-depth character fact sheet here’s one by Kaishos on DeviantArt).

Now, I have to admit, I don’t use character sheets. I think they can be helpful for more visual mediums like comics or films because you can answer “What is the character’s favorite color?” and then have them wearing green socks in every scene but, unless you’re being really really really particular, I don’t think someone writing a short story or a novel is going to note every important character’s sock color each time they change their clothes.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration of course, but you get the point.

Another option—the one that was actually my formal introduction to character writing—is to build your character up from two base questions:

- What is their greatest desire or need? Often, in shorter mediums, these are conflated or at least related.

- What is their greatest fear?

This approach was presented to me in a screenplay writing class and I think it works exceedingly well for films and short stories.

In both of these, you often have a shortened period of time to present the full character arc. As such, giving the character a single goal and focusing on a single fear allows for a clear and concise way of providing obstacles and accomplishments for your character that also harken back to who they are as a person.

Fears and aspirations are some of the most relatable parts of human life.

While, in most cases, you’re not going to have the character announce their desires and fears, you as the author should know them and know how they drive your character’s actions. If you build those inherent motivations into your character then they will immediately seem more real.

That being said, if you try to extend the single desire/fear model into a full novel or a longer running series then you run the risk of your characters seeming flat. They may become too single-minded and you might lose some of that nuance you’re really searching for. Instead, I tend to use something similar to, but broader than, the greatest desire/fear approach:

A compromise hierarchy.

Put simply, this is an expansion of the desire/fear model that helps you hone in on the most natural way for your character to act in almost any situation. A lot of the process here happens subconsciously for many writers and the more you work with your characters the more naturally it will come but, for clarity’s sake, I’ll run you through some steps to get started.

- Keep the “greatest fear” and “greatest desire” that you would have from the previous approach and pull out your character’s “greatest need” as something different.

- From here, create separate lists of even more fears, desires, and needs for your character. These can be anything from “afraid of spiders” to “wants to be an entomologist” to “needs to learn to trust people as much as insects” (I apologize for all my weird examples today).

- As the name would suggest, create a hierarchy for the fears and desires. What desire is your character willing to forego out of fear? What fear are they willing to face to get what they want? These decisions may not come up explicitly in the piece your writing but, understanding your character’s priorities on such an in-depth level will help their actions feel grounded in a very real, well-rounded identity.

- The list of “needs” is there more as an added little step than to play a part in the compromise. Depending on the tone and ending of your story, your character may fulfill their needs or not. However, I find that understanding how the character’s needs relate to their fears and desires helps to set up the appropriate challenges for the character in the narrative. Having needs that line up with a character’s fears or that go against a character’s desires is a great way to build underlying tension.

That’s pretty much it for my process!

A lot of this will come naturally as you write but, if you like to plan or if you’re feeling stuck, building up these lists and actively understanding the compromise can really help ground your character in reality.

A few quick notes:

I went through this process as if for the main character. More often than not, outside of perspective characters or lead supporting cast, you won’t need to go as in-depth (going back to the one fear/desire model for side characters can be a quick way of doing things) but it never hurts to make the outlying characters feel as real as possible so if you want to make a compromise hierarchy for multiple characters then go for it! Just remember:

Almost none of this will end up explicitly stated in your writing.

This is what I meant when I said to know more about your characters than your readers. While there are always exceptions—especially with more minor fears/desires—telling the reader exactly why the character is doing what they’re doing will, more often than not, ruin the dramatic effect of your writing.

If you want your book to feel real, don’t interject explanations of your character’s motives. Just have them act. That will feel real.

Again, none of these are hard and fast rules. You can always mix and match, use the approaches with mediums other that what I’ve suggested, and/or try something completely different! You should always do what feels best for you rather than trying to force someone else’s process onto your work. However, I hope that this brief survey of options has helped shed a little light on the matter!

Feel free to reach out if you have any questions!

May all be well,

Sarah E.

Pingback: Form Switching Part 2: From Screenwriting to Novel-Writing – For Page & Screen